Stave One

When I was about five or six, I found myself in handcuffs on the day after Christmas. I blame the ghost of Jacob Marley.

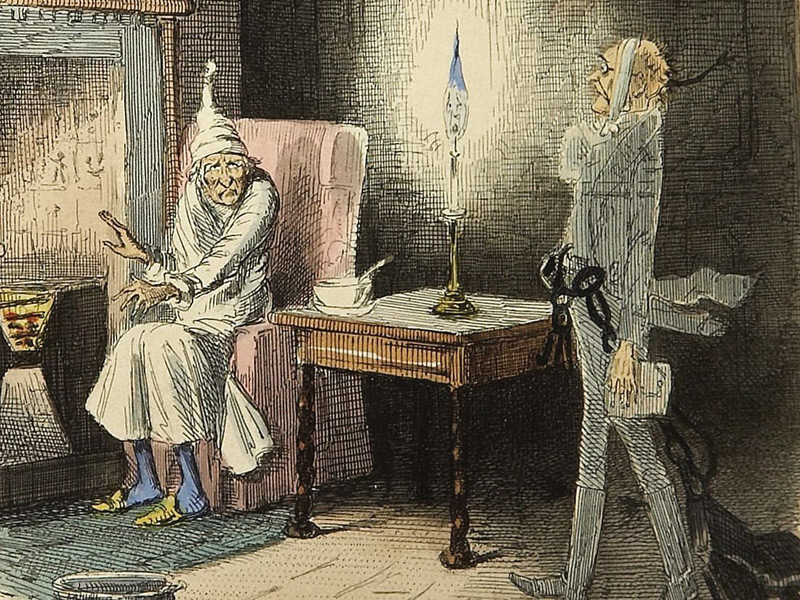

After big holiday gatherings with my mom’s side of the family at my grandmother’s house, some of us usually stayed the night. It was at her house that I awoke early as the adults, likely recovering from entertaining Christmas spirits the night before, slept in late. With the house to myself, I claimed control of my grandmother’s giant console television, and settled on an early morning broadcast of the Charles Dickens classic, A Christmas Carol. I watched as the miserly Ebenezer Scrooge humbugged this, that, and above all, Christmas. Taking a personal umbrage with his anti-Christmas sentiments, I was delighted to see him shrink in the presence of the ghost of Jacob Marley. If Ebenezer Scrooge was the bad guy, spooky old Jacob Marley was the protagonist. With one eye on the television, I started to root around the house for something that might pass as my own Jacob Marley costume. I settled on a bed sheet—a must-have in spectral couture—and a pair of handcuffs.

On the television, Scrooge was being visited by a parade of ghosts, none of whom inspired me as much as Marley with his clattering lock boxes and chains. Wrapped in the sheet, I closed one of the steel manacles around my ankle, ratcheting it closed until it would click no more. The three chain links between the cuffs weren’t as impressive as the lengths of chain that draped Marley’s ghostly form, but they’d have to do. I set out to haunt my mother out of her sleep.

“Mom. Lookit me, I’m a ghost!”

“Thassnice,” she mumbled, rolling over in the bed.

While on the television, a redeemed Ebenezer Scrooge embraced Christmas spreading good will to all in his path, I lost interest in my Marley costume. I dropped the sheet and fiddled with the handcuffs looking for the release catch. I was very familiar with the mechanics of handcuffs, having worn and successfully broken out of countless pairs of the plastic cuffs that were sold at CVS in police officer kits complete with a set of keys, sunglasses, and a badge. The keys were mostly for show as the cuffs always featured safety switch that would free the captive when engaged. The metal cuff around my ankle didn’t seem to have this useful feature. Panicking, I tried my best to pull the cuff open. It wouldn’t budge. Surely, my mom would know where the keys were. I returned to the room where she was sleeping.

“Mom, I was a ghost and I put a handcuff on my foot and now it won’t come off!”

“Thassokay,” she stirred, but did not wake.

Eventually, my family woke up and found me doing my unsuccessful Houdini routine in the living room. What followed was a frantic search for the handcuff keys, and a worrisome discussion cutting them off with a hacksaw. I started to imagine a future with the clinking manacle dragging at my foot. Eventually, someone called the police.

The police officer arrived looking authoritative and official. The badge, navy blue, and holstered revolver stood out in such contrast against the backdrop of my grandmother’s wood-paneled living room which was decorated for the holidays. The towering officer seemed intimidating at first, but I was put at ease when he squatted to my level. “How did this happen?” he asked, and my explanation was given. Naturally, he wanted to know where the handcuffs had come from. Someone explained that they were an artifact from my uncle, a former Military Policeman in the Navy. Satisfied with the answer, if not amused by my predicament, the officer produced a key ring with variety of small handcuff keys. Eventually, a matching key was turned and I was freed.

Stave Two

Despite my early experience with A Christmas Carol, it remained one of my favorite stories growing up. It’s probably, the story I’ve revisited the most, having first been introduced to it in the book, Best Loved Selections from Children’s Classics, through countless movie interpretations, as well as the original Dickens classic.

When I was in the sixth grade my school put on a production of the play, and I eagerly auditioned with the hope of landing the role of Scrooge or Marley. Instead, I was given the role of Scrooge’s nephew, Fred, the unflappable moral foil that challenges Scrooge’s cantankerous outlook. In most versions of the story he offers some beautifully eloquent lines like:

“though it has never put a scrap of gold or silver in my pocket, I believe that [Christmas] has done me good, and will do me good; and I say, God bless it!” But in my middle school version, Fred was only responsible for one short line.

I recited my line in all the rehearsals growing more nervous as the day of the performance approached. Admittedly, I wasn’t very good. I delivered my line in the colorless monotone of a 12-year-old reading from a textbook. I wonder now if my lousy acting was the reason that Fred ended up with one line in our production. Nonetheless, I was happy to play a part in one of my favorite stories. On the day of the performance, dressed in old-timey boots, an oversized blazer, and a shiny plastic top hat, I marched out on stage arm in arm with the girl playing my wife. Feeling the heavy presence of the audience, I nervously delivered my line:

“Christmas a humbug, uncle! You don’t mean that, I am sure?”

I stood there as the student playing my uncle nimbly lambasted me for my pro-Christmas stance. As Scrooge turned his ire to the kid playing Bob Cratchit, my wife and I exited stage right. My part over, I was able to watch the rest of the play. The kid playing Scrooge was good. He had an energetic stage presence, delivered his lines convincingly and certainly deserved top billing. Naturally, I loathed him.

At the close of the penultimate scene, where Scrooge sends the young boy to fetch a prize turkey from the poulterer, Scrooge exited the stage right instead of stage left. As a result, when the curtain rose on the last scene in which Scrooge pays a visit to the Cratchit house, Scrooge was on the wrong side of the stage. The scene called for Scrooge to knock on the front door, located stage left. In an effort to enter from the appropriate side, Scrooge—now dressed as Santa, as a result of an odd liberty taken by the director—decided to shimmy along the narrow space between the back of the cardboard set and the rear stage wall. Perhaps getting tangled in the curtain, Scrooge stumbled, pushing over The Cratchit family home. The audience roared with laughter as the leaning wall revealed an obviously flustered Santa-Scrooge. He stood there, arms out at his sides like a prison escapee frozen in a searchlight, as Tiny Tim, played by the tallest girl in our middle school, jumped from her chair to prop the falling set back into place, dropping her crutch in the process.

Scrooge eventually made it to the front door, and spent Christmas day with the Cratchit family as a man reborn. But the visit was awkward at best. He did try to destroy their house after all. It’s always been my opinion that immediately after standing and saving the family home, the not-so-Tiny Tim should have turned to the audience and delivered the closing line, “God bless us, every one!” at which point the curtain would close. While not faithful to the original story, I think most would agree that Tiny Tim’s sudden superhuman strength and miracle healing makes for a better ending than the original.

Stave Three

I’d try once more to participate in A Christmas Carol. In my junior year of high school, I attended a video media class that provided access to cameras and editing equipment. For a class project I created my own updated version of A Christmas Carol, inspired by Scrooged, a favorite translation of mine at the time. Called The Spirits of Christmas, it tells the story of a Scrooge proxy who deals drugs, but learns the error of his ways after a Christmas Eve visit from four ghosts. In it, I play the Scrooge and Marley characters, as well as The Ghost of Christmas Past. I also provided the makeup effects, and plinked out some of the soundtrack on a Casio SK-1 keyboard.

It’s a horrendous 8 ½ minutes of video that hardly makes sense. Yet in spite of its excruciating amateurishness, it earned me a high grade in the class and won first place in a statewide video competition. I bet that the judges ate up the ABC Afterschool Special brand of morals it employed. My media teacher submitted the video to the competition without my knowledge, only telling me about it after the video was nominated. While I’m thankful that he believed in it, especially since the contest cash prize paid for my first year of college, my eyes water in embarrassment when I watch it now. Its overly melodramatic tone and my awkward attempt at playing a tough guy are truly cringe-worthy. If you have 8 ½ minutes to waste, feel free to cringe along with me. Consider it my Christmas gift to you, internet.

Stave Four

I no longer feel the need to participate in A Christmas Carol. Sure, my choice to break this article into four staves is a device borrowed directly from the Dickens classic. But this is the last time, I promise. I’m satisfied with leaving the interpretations to the experts. There are so many great adaptations for fans of this classic, many of which are available online like the 1910 silent film version produced by Thomas Edison, the 1951 film Scrooge starring Alaister Sim in the title role, or the 1970 musical starring Albert Finney in the lead and Alec Guinness as the Ghost of Jacob Marley. Notably, Guinness’s take on Marley was seven years before his role as the Ghost of Obi-Wan Kenobi. Scrooge has been played by the likes of Reginald Owen, Mister Magoo, Frederich March, George C. Scott, Scrooge McDuck, Michael Caine, Patrick Stewart, and many, many more. There are also countless numbers of interpretations that use the classic as an outline, like the 1988 film Scrooged, or the 1979 made for TV movie, An American Christmas Carol, starring Henry Winkler. I can’t speak to the quality of the latter, but it has to be better than my take. In 1951, the BBC radio produced a version with Alec Guinness as Scrooge, 20 years before his scene-stealing turn as Marley on film. In America, Lionel Barrymore provided the voice of Scrooge in Christmas radio broadcasts from 1934 to 1953. Notably, Lionel Barrymore, played the equally miserly but irredeemable Mr. Potter in Frank Capra’s 1946 classic, It’s A Wonderful Life. I do like to revisit the original from time to time, and thanks to its public domain status the story is easy to find online, in ebook, and audio book formats, video and, radio productions.

This year, A Christmas Carol celebrates its 170th year and it remains as relevant today as it was in 1843. It condemns greed and materialism while conveying empathy to the disadvantaged. I, for one, am a sucker for stories that rally for the little guy. Additionally, Dickens has been credited with putting the merry back in Christmas after an era of understandable somberness. This might explain its constant revival. Christmas is often a very stressful and unhappy time of year. A reminder of what one doesn’t have rather than what one does. A Christmas Carol relies on its sentimentality to refocus the riches of the season on family, togetherness, charity rather than accumulation of stuff. It remains one of my favorite parables because it presents the idea that we have control over our own respective destinies and the power to right our wrongs. Also, it explores the idea of time travel and the power of nostalgia, two themes that I always appreciate.

This year, the New York Public library hosted a reading of A Christmas Carol by Neil Gaiman, an author at home with the macabre who delivers entertaining dramatic readings of his own stories. As fan of both Gaiman and Dickens, I was doubly disappointed to have missed the sold-out event. It was also stated that Gaiman would be following notes and reading prompts made by Dickens himself.

The day of the reading, Twitter was flooded with photos taken by those lucky to attend the event. They showed that Gaiman delivered the reading dressed as Dickens, complete with top hat and beard. It was hard not to bemoan the lucky bastards that were able to attend. However, I was thrilled to find that the New York Public Library has made audio of the reading available online. It’s not as good as being there but, as evidenced by my history, it’s probably better off that I experience the story from afar.

A Christmas Carol, read by Neil Gaiman

Read what other League of Extraordinary Bloggers members had to say about this week’s theme:

The Goodwill Geek reminds us that Christmas is about family.

Cool & Collected battles a legion of Christmas praying mantises.

That Yellow Duck gets nostalgic about monkeys hippos and ducks.

Talk Junk