Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is in vogue these days. People toss around phrases like “my OCD is acting up,” or “I’m so OCD” as a way to express their fastidiousness or propensity for cleaning, safety, organization, matching, and the like. OCD is this season’s hottest new accessory that screams individuality. Like a fun pair of non-prescription glasses or a jaunty vintage hat, OCD is the perfect adornment to round out any ensemble. Please forgive my snark, but I’ve worn this cumbersome accessory since I was a child. I have spent most of my life wishing to be rid of it, and always worry that someone might notice me wearing it. So the idea of someone willingly donning OCD just seems ludicrous to me. It strikes me that I don’t think I’ve ever heard someone say “my cancer is acting up,” or “I am so asthmatic.” This is not to trivialize cancer or asthma or even liken OCD to either, rather to emphasize the point that psychiatric diagnoses are much more easily manhandled, bullied, and manipulated. I find it hard not to be personally offended by people who casually claim that they have the disorder, when what they generally mean to convey is a proclivity for organization, and perhaps a strong preference for symmetry. I feel conflicted about whether I should fault the media for inappropriately characterizing the disorder or those who unquestioningly adopt it. Hence, the purpose of this post is to better understand this conflict.

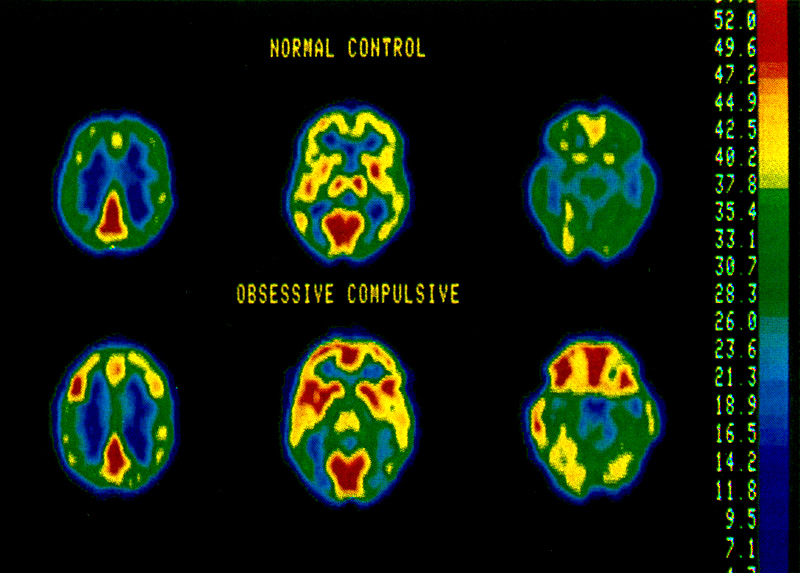

OCD is an anxiety disorder that causes a significant amount of distress to those who suffer from it. Enjoyment derived from arranging books in alphabetical order, or organizing your closet is not OCD, and suggesting that it is can be invalidating to those who are legitimately plagued by the disorder. Obsessions are often intrusive thoughts that contain distressing illogical or taboo subject matter that can only be relieved by the irrational need to perform some kind of behavior (i.e., compulsions). Those with OCD are aware of the irrationality which only causes further distress. The content of the intrusions experienced by those diagnosed with OCD are well within the typical continuum of human thought. In those without OCD, intrusions are a mere blip in one’s stream of consciousness. While in the OCD diagnosed, the intrusion gets stuck on a loop and amplifies itself.

Often, movies and television broadly portray OCD sufferers as chronically fastidious germaphobes with strange washing and checking rituals. This is the case in many instances of OCD, but it’s a gross oversimplification. These media portrayals often focus on OCD’s greatest hits, and neglect the b-sides. Like most psychological disorders, OCD is a complex continuum of symptoms that manifest in a number different ways. Some of these attributes don’t always play as well for the camera and thus are underrepresented in the media. It makes sense then that people view these simplified media examples and identify with it to some degree. In it, they see their own organizational inclinations, or anxious need to double-check the stove before going to bed. This, as well as snippets of information gleaned from internet lead to inaccurate self-diagnoses that might prompt someone to claim that they are “so OCD” or any number of other misrepresented psychiatric disorders.

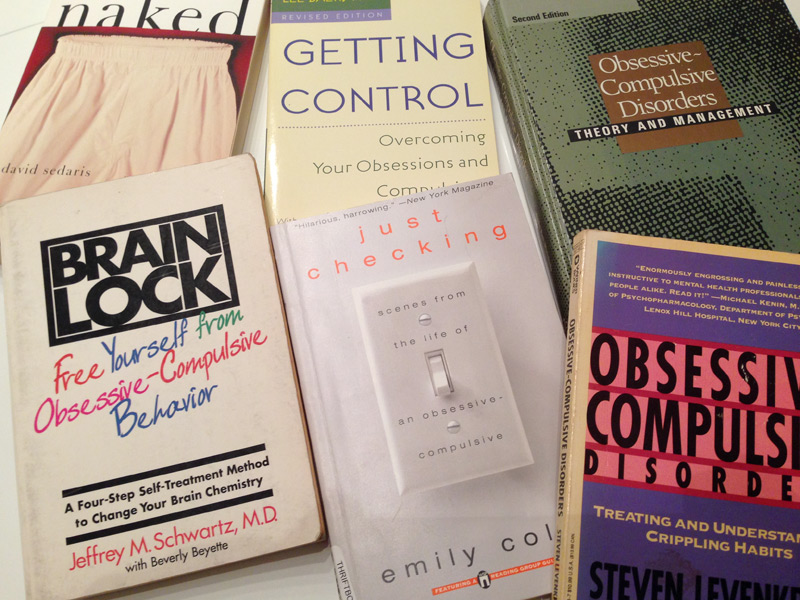

Thankfully, not all depictions of OCD are the diluted misrepresentations so often put forth by film and television writers. In the video below, comedian Maria Bamford plays her experiences with the disorder for laughs in her Anxiety Song routine. In his essay “A Plague of Tics,” author David Sedaris describes being tormented by an elaborate series of compulsory tics that left him feeling alienated and exhausted, illuminating the blurred line of the psychiatric diagnostic continuum. More recently actor and writer, Lena Dunham has drawn from her real-life experiences with OCD on the television show Girls with a frighteningly honest depiction. I commend each of them for bravely sublimating their troubling experiences into these accurate and creative outputs. Depictions like these help to educate the unknowingly misinformed, as well as to diffuse stigma surrounding mental illness. I only wish such examples where available to me 30 years ago. They would have certainly helped me feel less alone.

In addition to these more informed depictions of OCD, there has been a growing conversation regarding the trendy overuse of OCD. Writer Mara Wilson deftly addressed the subject in her article “4 Things No One Tells You About Having OCD.” Similarly, in his article for Psychology Today, author and OCD Foundation spokesperson Jeff Bell clarifies that OCD is not an adjective. Their input on the subject bears a level of credibility as both Mara and Jeff have personal experience with OCD.

It’s important to know that people with OCD do not derive pleasure from their compulsions. We may feel temporary relief by engaging in them, but ultimately the experience is distressing and time-consuming. Sufferers understand that the thoughts are unrealistic and that the behaviors are excessive, but are compelled nonetheless. The basic rule of OCD is that it begins to get in the way of normal functioning, and that it does not feel good. People with legitimate concerns can self-rate themselves using the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS). The Y-BOCS is a tool used in clinical practice; it should not serve as your official diagnosis. Sure, anyone can use a stethoscope; it doesn’t make us all cardiologists. For an official diagnosis I recommend seeking the help of a licensed mental health practitioner. The International Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Foundation provides a helpful listing of treatment resources.

I’ve been in therapy with a psychiatrist I trust for nearly 13 years, and I continue to educate myself about OCD. Finally, I feel in control of myself. Today, when intrusive thoughts enter my mind, I can recognize them for what they are, and let them go. I am able to harness my obsessive energy to serve me in my trade as an illustrator and graphic designer, and in my hobby as a collector of pop culture ephemera and knowledge. The corners of my mind that were once cluttered with terror, dread, and guilt are now occupied by much more pleasant thoughts.

As a teenager I found myself in a therapy group where I met a fellow OCD sufferer whose irrational fear of contamination was so great that she’d taken to carrying a spray bottle filled with rubbing alcohol. Whenever the contamination thoughts would take hold, she would mist her hands with the alcohol to rid herself of her perceived contaminant. This compulsory ritual only served as a brief reprieve from her mental anguish. Moments later the thought of contamination would return, and she’d feel compelled to spray her hands again. Trying to resist the urge to clean her hands would only increase the volume of the obsession. At the root of her obsession, she believed that failing to rid her hands of the contaminant might lead to the death of a stranger, or worse a loved-one, by passing it on to them through a communal object like a telephone receiver or doorknob. The obsession was really more about her fear of killing someone than a need to clean. Once the intrusive thought enters the mind, it spirals out into the darkest recesses of the worst possible outcomes, seemingly impervious to intellectual reasoning and logic. As a result of her compulsive hand sterilization regimen, the skin of her palms was burned and splitting at the joints from constant exposure to rubbing alcohol. Despite the raw open wounds and defying logic, she continued to spray her hands with alcohol because her self-harm was far better than the alternative scenario that her obsessive thoughts threatened.

Despite our disparate manifestations, the spray bottle lady and I bonded over the internal unrest our common diagnosis caused. My brand of OCD leans more into the primarily obsessional territory, which means that I’ve enjoyed just as much of the cognitive turmoil with less of the overtly recognizable compulsions. This is not to say that I have it any easier than those with outwardly presenting compulsions. I have struggled with contamination obsessions, though to a lesser degree than spray bottle lady. I’ve also been troubled by checking rituals and the overwhelming need to repeat particular tasks until they were completed satisfactorily. Similarly, I was often convinced that I had contracted a disease or that I was actively sick or dying and, moreover, that I would potentially pass the disease on to someone else. Anyone observing from the outside would usually be hard-pressed to detect anything awry with me.

My first intrusive thought came to me when I was eight years old. It blinked into existence suddenly, as if a switch had been thrown into the on position. One afternoon, I was playing with a toy gun that shot suction cup darts. I remember pointing the plastic pistol at the back of my father’s head. I had no intention of pulling the trigger, though if I had, the dart would have simply bounced off of my father’s head causing no true harm other than earning me an admonishment. My father frequently made it clear that I was never to point a toy gun at him, as it triggered memories of him of his time in Vietnam. In hindsight I have to wonder why he provided me with both the gun and the idea in the first place. Not fully understanding the emotional complexity of his rule, I took the opportunity of his turned back to disobey raising the toy gun. As I aimed two words formed in my mind. Kill him.

Alarmed by the combination of words my imagination had just strung together, I lowered the toy gun. I knew that I didn’t want to kill my father. I didn’t even really want to shoot him with a suction cup dart, yet my mind said otherwise. I feared that the thought might somehow overpower my will. Silently I repeated the words don’t kill him, don’t kill him; a silent prayer as a futile effort to un-think my first thought. I ruminated, trembling, breaking into a cold sweat and fighting back an overwhelming feeling of nausea. The more I wanted to be rid of the thought, the deeper it would root itself into my consciousness.

From that point on, I became plagued by similar distressing thoughts with an increasing frequency. The thoughts came like a crow entering a room by crashing through a window pane. As it fluttered around the room knocking pictures off the walls and colliding with lamps, I’d try my best to ignore the trapped bird. Its cawing and bared talons demanded my unbroken attention. Inevitably, all of my cognitive energy would be focused on trying to find a way be rid of it.

The thoughts were often violent, sexual, or blasphemous in nature. Terrified, I became convinced that I was sick or evil and that I might potentially act on one of the thoughts, harming someone or myself. I became uncomfortable around knives or scissors, worrying that I might lose control and harm a family member. Most of my time was spent under the weight of a crushing guilt. I began frequently napping, perhaps out of exhaustion from the roiling cognitive activity, if not as an attempt to temporarily escape the turmoil.

Eventually I confided in my mother with that initial thought, admitting that I was worried that I might kill my father. She explained that it was normal to have all kinds of thoughts, good and bad, and that it was doubtful I would ever act upon them. Once the thought was shared with someone else it felt as if the switch was flipped back into the off position. It vanished as abruptly as it had come. Suddenly, I felt relief and absolution of my perceived sin. In my confession, I had found my compulsion. It wouldn’t be long before another thought would begin to gnaw at me. Again, I would need to neutralize the anxiety by confessing the thought. I perfected the confession compulsion during my dating years. I’d worry that I would destroy my relationship by impulsively acting upon any attractions outside of the relationship, and then would have to confess that worry to my girlfriend. While these disclosures would alleviate my compulsions, they were wounding people that I cared for, ultimately leading to many years of heartbreak.

As is the case with most human development, my manifestation of OCD seemed a perfect mix of genetics and environment. While neither of my parents has been diagnosed with OCD, my father and his family certainly could have been. I have clear memories of my paternal grandmother excessively neat-nicking the entirety of her house down to the barely perceptible pills on the carpet. My father continues this tradition with checking compulsions and he even has an element of confessionalism around his experiences in the Vietnam War, much of which I was a vessel for at a young age. My Catholic upbringing taught me monotonous ritualization as a means to repent for my sins. After all, according to Catholic logic, if I felt bad for peeking into a nudie magazine, an even amount of Hail Marys would unequivocally make it all right in the eyes of the lord. Additionally, both sides of my family are strongly predisposed for addiction which is in some ways a disorder of impulse control or compulsion. I’ve struggled with how much of my behavior is learned versus genetic knowing that I’m ideally primed for OCD. Major stresses often trigger genetic vulnerabilities in the right environmental context. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that my OCD had a clear onset around the time I underwent hip surgery, spent months in a body cast, and lived between my sometimes obsessive, sometimes compulsive parents.

It was only years later that I’d be diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder. The official diagnosis was helpful in that I no longer felt uniquely crazy but part of a crazy club. In the decade that followed, I’d see a number of psychiatrists with little to no relief. For a time in my later teens, I was prescribed many combinations of medications that did help keep my OCD at bay, but had the unfortunate side effect of blunting my personality. Frustrated by feeling numb, I’d usually discontinue my treatment cold-turkey and end up in a worse state than before. It wouldn’t be until my late twenties that I’d find a therapist I felt comfortable with, and make significant progress in my struggle against OCD.

I’ve spent too much of my life feeling defective and ashamed of my OCD. Sharing my experience here is no easy task, but I do so in hopes that it might help a fellow sufferer while contributing to the informed mental health conversation. My bruises and victories in this fight have been hard-won, so it’s natural that when I hear a casual proclamation like “I’m so OCD” that I struggle not to respond with, “That’s my disorder, give it back!” However, I am realizing that it might be more productive to educate people about the disorder rather than to admonish. OCD isn’t a whimsical personality trait. It’s a big bad wolf that I wouldn’t wish upon anyone’s doorstep.

Certainly, there are greater things to bristle over. For instance, when not being misunderstood, mental illness is often only discussed in the wake of human atrocities like mass shootings, which just stir the general public into frenzies not unlike torch-wielding angry villagers. Clearly there needs to be an improved understanding of mental health in general especially since lifetime prevalence of mental illness in the United States is 55%. That’s more than folks who have a chronic physical illness like diabetes, heart disease or asthma. As a society, it’s important that we co-exist with a basic level of understanding and empathy. It’s a crowded world, and we should all try our best to not step on anyone else’s toes (or diagnosis for that matter). But maybe I’m just overthinking it.

Talk Junk