If you grew up ensnared in the hypnotic glow of 1980s television, you probably remember Max Headroom, the “computer generated” TV personality from the near future. The charismatic icon with the glitchy stammer was a ubiquitous presence in the mid to late 80s, mostly due to his time as a spokesperson (or spokeshead) for Coca Cola. The soft drink giant tried diligently, but unsuccessfully, to peddle their New Coke formula capitalizing on Headroom’s trademark speech impediment to beckon people to Catch the wave. Unlike his contemporaries, the California Rasins, The Noid, and Spuds MacKenzie, Max Headroom enjoyed a career beyond advertising. He starred in a number of television programs, appearing on David Letterman, Sesame Street, and the cover of Newsweek, parodied on the cover of Mad Magazine, and providing vocals for the Art of Noise’s “Paranoimia” to name a few. The Max Headroom cult of personality was inescapable. In the 80s, he was as we were: neurotic, fractured, and hyperkinetic in the dysthymic wake of the 70s, and more than a little defiant. These quirks combined with a quick wit created the perfect avatar for the increasingly distracted MTV generation.

Developed in the UK, Max Headroom was the world’s first “computer generated” TV host, a polished but twitchy talking head (literally) within the confines of rotating multicolored wire-frame cube. In reality, this computer generated effect was achieved through practical special effects makeup, a fiberglass suit, analog animation, and clever sound and video manipulation. The true soul of Max Headroom falls squarely on the shoulders (again, literally) of actor Matt Frewer, who has since become a sci-fi mainstay appearing in things like The Stand, Taken, Eureka, Falling Skies, and Orphan Black. Frewer’s wry and sometimes improvised performance combined with innovative special effects birthed a strange and idiosyncratic pop icon.

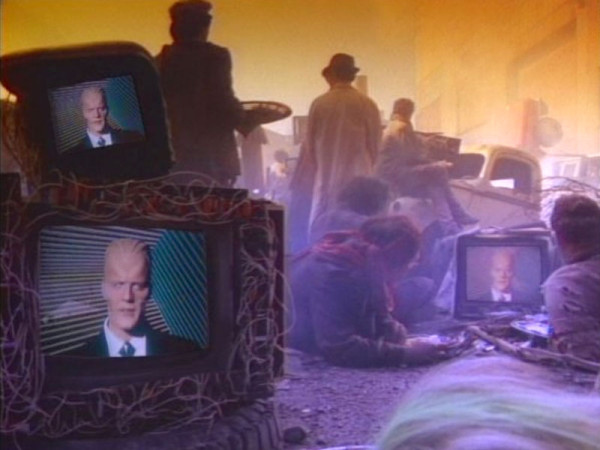

The Max Headroom concept was originally developed to serve as the eponymous veejay for a Channel 4 music video show. In an effort to build a character mythology, Max was retrofitted with an origin story in the form of a telefilm. The movie, Max Headroom: 20 Minutes Into the Future, is a dystopian fable of the very near future (in 20 minutes to be exact) when television executives rule as a shadowy oligarchy and the proletariat are encamped on the fringes of society lit by barrel fires and glowing televisions. The story follows Edison Carter (Matt Frewer), an investigative reporter, on a crusade of truth through a gritty cyberpunk futurescape. The deliberately chosen names of Max’s human iteration prime the viewer emotionally: Edison, as in bringer-of-light and Carter, who struggled to shepherd a super power out of moral corruption. Edison discovers that his own employer, Network 23, is responsible for Blipverts, a highly concentrated televised advertisement that is causing viewers to explode. Discovering that Edison is about to expose the Blipverts story, Network 23 dispatches a pair of Road Warrioresque goons to intercept the meddling reporter. Commandeering one of the goon’s motorcycles, Carter flees only to crash the motorcycle into a barrier, rendering him unconscious.

As troublesome as he is for the network, Edison Carter is their star reporter and a ratings juggernaut. In an effort to maintain his ratings, the network’s resident computer genius/mad scientist proposes they create a digital copy of Edison Carter to control and censored as needed. Downloading his consciousness into a computer to render a digital likeness of Edison, Max Headroom is born. He blips to life stuttering the phrase M-M-Max Headroom, an echo of the clearance barrier which read MAX. HEADROOM: 2.3 M, the last thing that Edison Carter saw before being knocked unconscious. The surrogate is buggy, uncontrollable, and too rudimentary to actually pass as the real Edison Carter forcing Network 23 to abandon the Edison Carter replacement plot.

The real Edison Carter eventually regains consciousness, flees, and finds himself back on the story while his cyber surrogate is acquired by a pirate TV station and reintroduced into the broadcast stream. Max Headroom is essentially Edison Carter’s digital id running rampant. Max is able to traverse the broadcast signals as he pleases, blipping onto screens throughout the futurescape to offer his stammering, pitch-shifted commentary. Edison and Max combine efforts as two parts of a whole, the id and the ego, to expose Network 23’s malevolent plot.

The British telefilm was later re shot as a pilot for a short-lived television show that aired between 1987 and 1988 in the US. The pilot is mostly faithful to the source material, but does suffer from Americanization. Stylistically, the UK telefilm, the US pilot, and subsequent episodes are a cross between Mad Max and Blade Runner, but on a budget. The tone is dark, atmospheric, and paranoid, proposing that the viewer trust no one, years before the X-Files. With the exception of the use of cathode ray tube TVs and computer monitors and a wonderfully synthesized soundtrack, it doesn’t really feel dated. It’s likely that if it were made today, the flickering televisions would be swapped out with smartphones and tablets to illuminate the hypnotized faces of the societal fringe-dwellers. Still, these archaic era cues work as a retro-future stylization. The movie and series both hold up as decent works of sci-fi exploring themes of artificial intelligence, cyberconsciousness, and corporatocracy, all of which are still relevant. The series, which ran on ABC, continued its satirical jabs at the television industry. It pondered subjects like exploitative reality programming and the press’ ratings driven focus on violence and tragedy, effectively predicting the schadenfreude future of real world television. After only 14 episodes, the show was cancelled. Perhaps ABC was too thin-skinned to tolerate such jabs from within its own camp.

Like most sci-fi, the show introduced the mainstream public to new ideas, even challenging the viewer to be mindful of the man behind the curtain. Such themes and expectations may have been a bit too heady (Ha, get it?) for a network television audience acclimated to numbing programming. In an extreme incident, the show did inspire an anonymous signal hacker to interrupt a broadcast of Doctor Who airing on Chicago’s WGN-TV network. The broadcast pirate, wearing a Max Headroom Mask, delivered a brief yet disturbing message before vanishing as quickly as he’d appeared. The party responsible for the incident was never identified, and a select number of Doctor Who fans in and around Chicago area have never been the same. The incident is on YouTube, but be warned that some things can not be unseen.

In the telefilm and the series, Max Headroom was the conscientious voice of a society lost in the shadow of nefarious corporate endeavors. Ironically, he will most likely be remembered for appearing in liquid diabetes advertisements for a corporate titan. I suppose everyone has a price, even fictional artificial intelligences. Though, maybe Max Headroom’s sarcastic tone is the very thing that lead to the failure of New Coke. If this is the case, I choose to believe that he was intentionally acting as an agent provocateur.

In 2007, Max Headroom re-emerged on Channel 4 in the UK to announce the channel’s transition from analog to digital in a series of ads. Though visibly aged and a bit more crotchety, Max’s glitchy charm was intact and his sense of humor was sharp as ever.

Luckily, Max has found a way to entertain and enlighten younger generations having found his way onto the internet. At the moment, the original Channel 4 telefilm and ABC series is available on YouTube, as well as on DVD. It’s just the thing for us fringe-dwellers who are bored with the regularly scheduled programming.

Talk Junk